The Basics

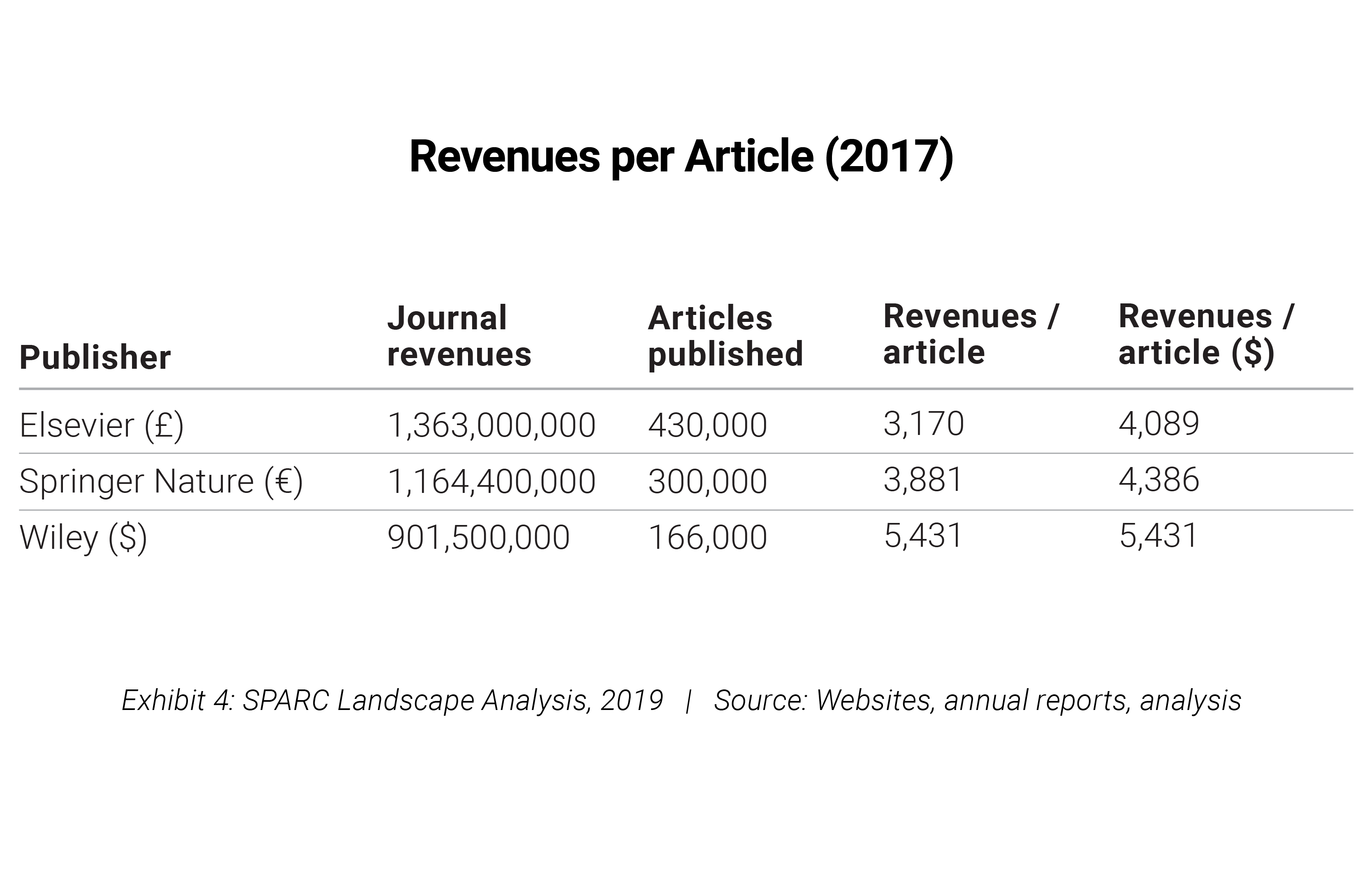

Wiley is the smaller of the three main journal publishers. It publishes about 2,300 journals, so – in terms of titles – it is very close in size to Elsevier. Journal revenues, however, are much lower: in the fiscal year that closed on the 30th April 2018, journal revenues totaled $901.5 million. This number is driven by the lower number of articles published: the company claims to publish only one third of the 500,000 articles submitted every year, translating into about 166,000, substantially fewer than the 430,000 articles which Elsevier publishes; in terms of revenues per article, both Wiley and Springer Nature now appear to earn more than Elsevier (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4

Research is the largest activity within Wiley, accounting for 52% of revenues (largely journals, with a small contribution from Atypon). Books account for 34%, and the balance derives from learning services (increasingly digital, but not exclusively). The company is publicly listed and led by an independent Board, but the Wiley family is still involved.

What is Wiley’s strategy?

Wiley’s acquisition in 2016 of Atypon for $120 million, at first glance, seems to underline management’s belief that the traditional subscription business model will survive. We have modelled the deal based on the data made available by Wiley, supplemented by interviews. Based on these data points, Wiley would have to believe that Atypon could grow its standalone cash flow (i.e. the cash generated by the business for its previous owners, with no synergies) by 2% in perpetuity to justify the price.

We doubt that Wiley’s management is just taking unwarranted risks. Wiley could justify a very expensive valuation because of its synergies with Atypon. Our interviews suggest that Wiley never achieved a satisfactory digital distribution. Interscience was heavily overstaffed with as many as 400 FTE employees and may have cost Wiley as much as $60 million/year. If Wiley could save only two thirds of its Interscience costs and it lost all external revenues, the deal would still make sense financially. Of course, this conclusion hinges on several assumptions. The greatest sensitivity is to the actual costs savings, which in turn depend on the number of Interscience employees at the time of the deal. If that number is directionally correct, then all other sensitivities are relatively minor. If we are correct, Wiley has invested substantial resources to eradicate an operational problem. This makes a lot of sense financially and operationally, but it also means that management has had less time (and resources) to think, develop, and execute a data strategy.