The Basics

Elsevier is the name usually attributed to RELX Group’s Scientific, Technical, and Medical business. RELX Group (known until 2015 as Reed Elsevier) is a London-based provider of information, data, and analytical services for corporate, professional, and academic customers. Elsevier is RELX’s largest area of activity, accounting for 33.7% of its revenues but 40.5% of its profits. It is also the most profitable business within RELX’s portfolio, although Risk & Business Analytics is a close second.

How well does Elsevier compete in journal publishing?

Elsevier is not the largest publisher of STM journals in terms of titles (Springer Nature Group publishes about 3,000 titles), but it has the largest journal revenues: Springer Nature Group had 2017 revenues of €1.64/$1.9 (at an exchange rate of 1.16) billion, but about 30% of that was books, leaving journal revenues at about $1.333 million, well below Elsevier’s estimated $1.8 million.

Elsevier, however, attracts a disproportionate amount of attention within the academic community because of its profitability and its business practices. Elsevier operates at a 37% reported operating profit margin compared to Springer Nature which operates at a 23% margin. Elsevier has often pursued tone-deaf business practices, which have been viewed as a land grab by the academic community. For example, Elsevier has refused in many countries to sign offsetting deals for publishing Open Access articles in subscription journals and has also engaged in relentless lobbying activity in both the U.S. and Europe to extend copyright in novel directions. Elsevier now routinely bypasses librarians and attempts to strike deals with other offices within large academic institutions. In response to the concerns of its critics, Elsevier would argue that it enjoys record revenues and profitability for the following reasons: it manages itself well, researchers want to be published in their journals, it funds activities for Open Science and for integrity in research more than any other publisher, and it sells data analytics services because the academic and research communities need them.

Both sides of this argument miss an essential point. The adversarial relationship between Elsevier and academic librarians (and some researchers) is an anachronism and a throwback to management practices that have long disappeared in virtually every other industry. The existence of SPARC, the periodic Elsevier boycotts from some groups of academics, and the announcements from European consortia (and, more recently, from the University of California) willing to lose access to Elsevier journals rather than agree to requested price increases all point to a flaw in how Elsevier (and some competitors) are run.

Historically, Elsevier has pursued price increases in the region of 5% annually, and justified this request with the parallel 5% growth in articles it publishes. This argument is flawed for two reasons: it assumes that there are neither productivity gains nor scale economies anywhere in the business. The first part of the argument is surprising – if productivity at Elsevier does not rise, then management is not doing its job properly – and the second part of the argument is wrong – administration or IT staff does not rise just because more articles are published. In light of the financial pressure on academic library budgets, refusing to pass along some of the savings is strictly a commercial and business decision, but it does invite retaliation from customers when possible. We have seen that Elsevier is effectively reinvesting some of these gains in new products and services which offer no benefit to libraries, as they are targeted to other users within universities (and even to completely different customers). In other words, librarians are asked to bear the financial burden of investments which will benefit some other category of customers, as well as the shareholders and management of Elsevier.

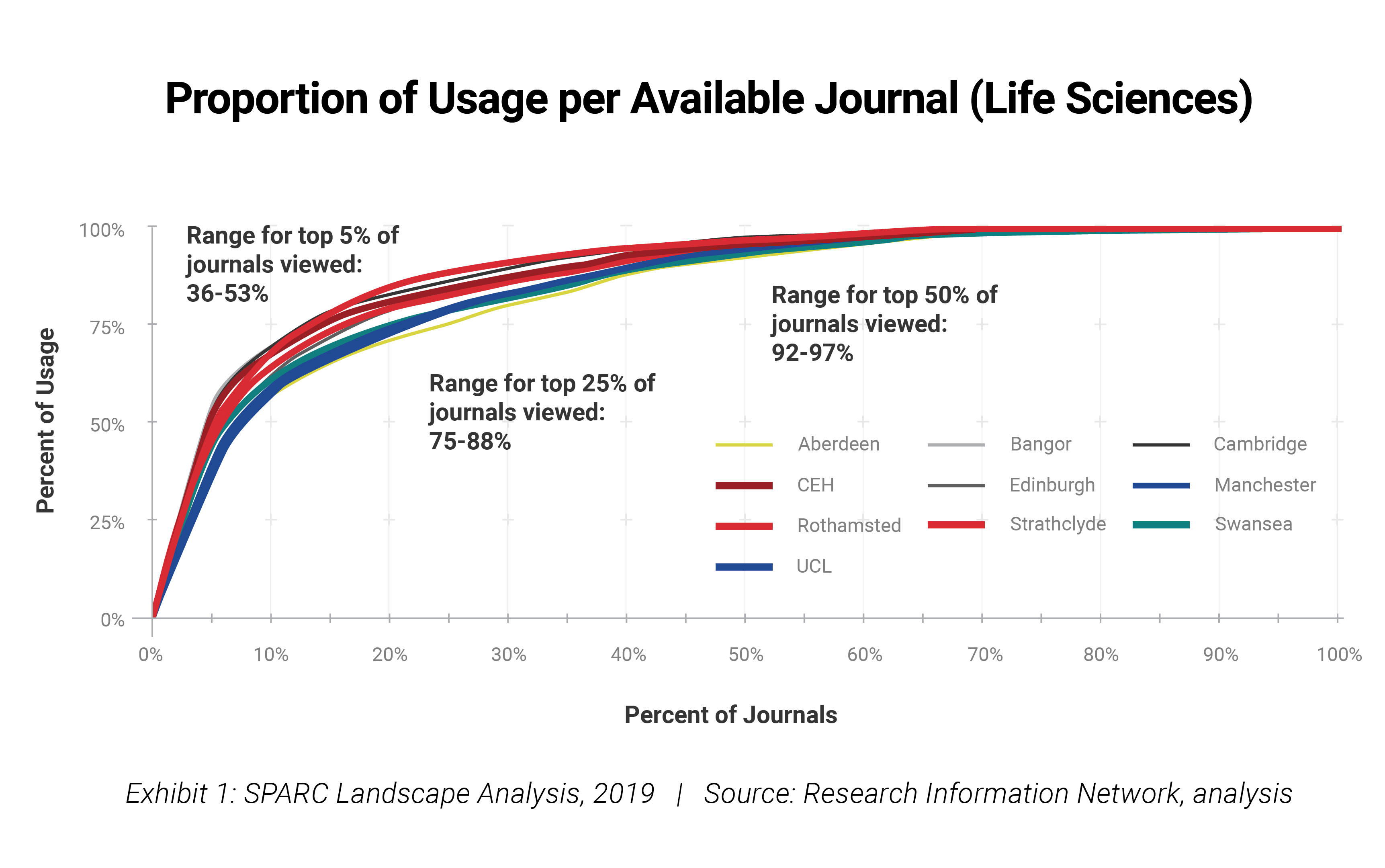

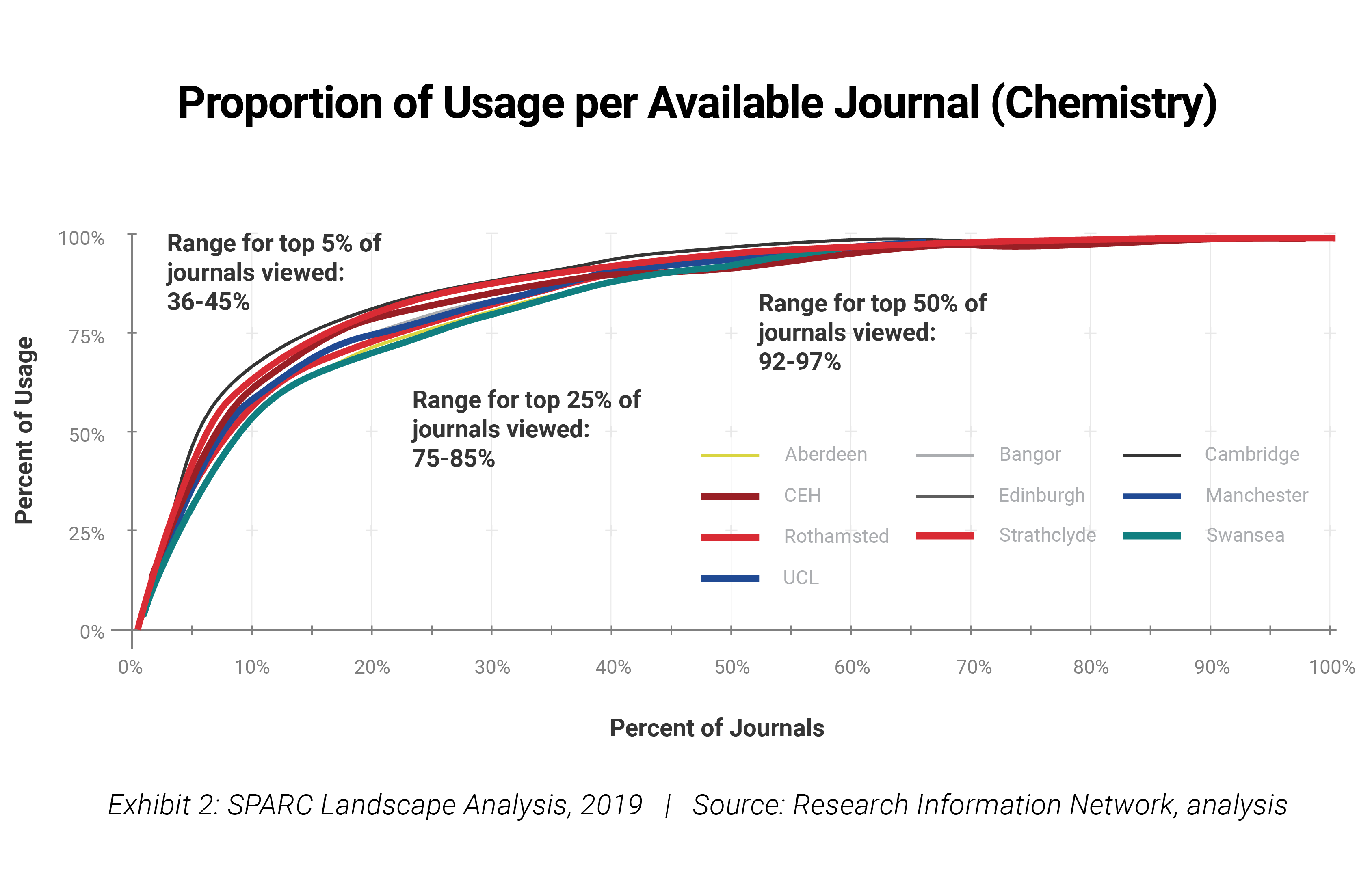

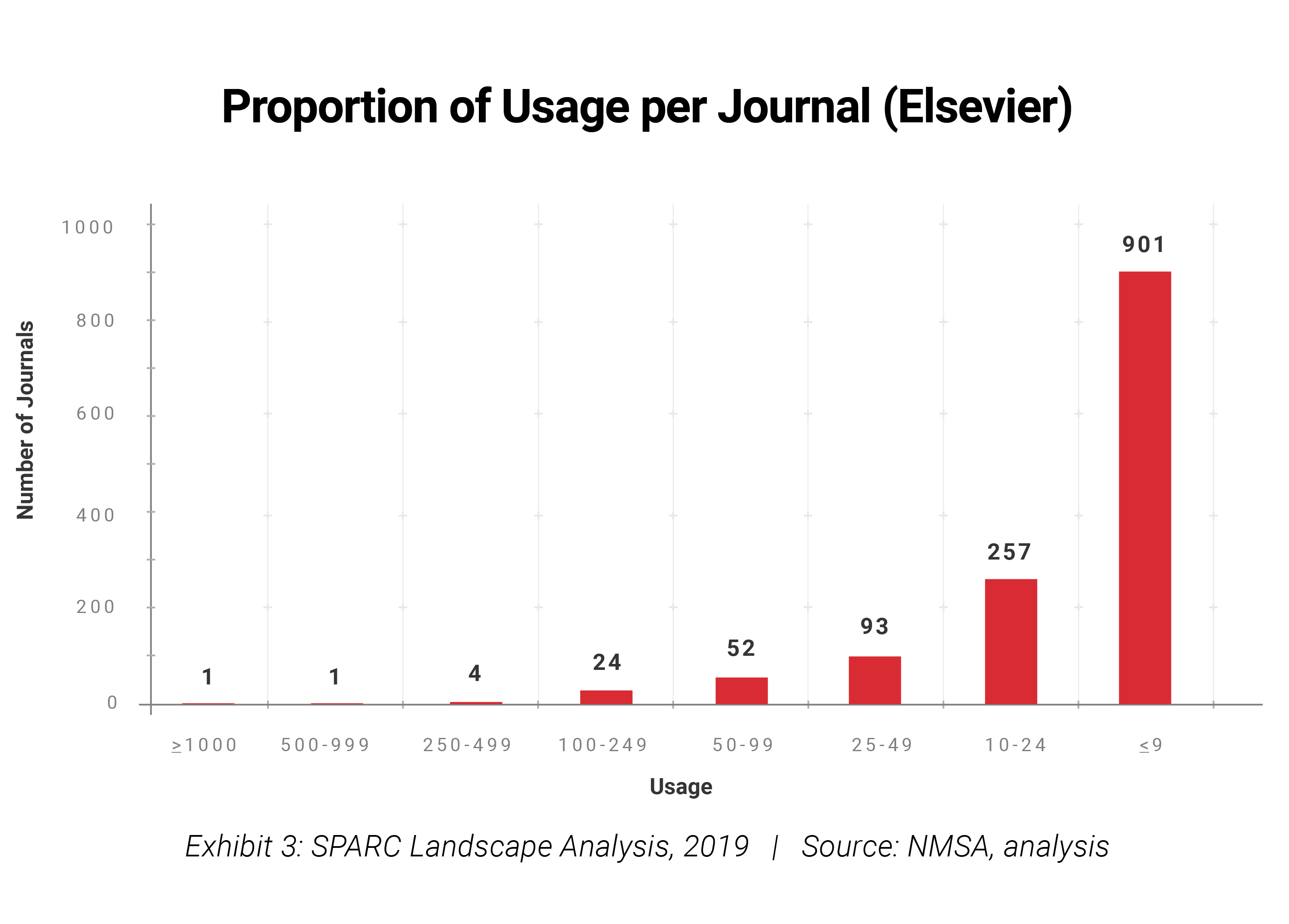

Another issue with the request for an annual increase based on a larger number of articles published is the quality of those additional articles. Just because it is additional research does not make it equal in quality. In general, a large amount of published research may end up of limited or no use to subscribers. Data released by ten UK universities on readership in chemistry and life sciences journals show that 50% of journals account for 5 to 10% of all article readership (Exhibits 1 and 2). This pattern applies to Elsevier journals as well: when New Mexico State University decided in 2010 not to renew one of its collection contracts with Elsevier, it published the data relating access to readership for the journals included in the collection (Exhibit 3). In the absence of obligations for leading journals to add articles at a pace that is at least in line with the overall growth rate of articles published, there is a significant risk that the average “quality” of the articles will decline. This, in turn, is a contentious issue for librarians asked to fund a growing number of journals and articles with no guarantee that their quality will be adequate.

Exhibit 1

Half of the journals in Life Sciences account for 5 to 7% of articles readership among ten UK universities…

Exhibit 2

…and a similar ratio applies to chemistry journals.

Exhibit 3

The same distribution applies to Elsevier journals, as NMSU reported that 901 journals (out of 1333) were accessed once a month or less in the nine months before contract expiration.

Elsevier and the future of scholarly publishing - what strategy?

With this background in mind, it is no surprise that Elsevier is thinking about what the future may have in store. In spite of the fact that scale economies in the business would favor acquiring other publishers, in the past few years, Elsevier has not pursued significant acquisitions in academic journals. The company has invested, instead, to acquire platforms and tools which would broaden its range of products and allow the company to attract new customers beyond its traditional base of research libraries. In fact, in a 2015 investor presentation, Elsevier explicitly indicated its intent to increasingly serve university administrations, funding bodies, and governments with tools aimed at estimating and improving the productivity of research and optimizing funding decisions.

These investments have not been huge, but have been much larger than would make financial sense. Press reports indicate that Mendeley and SSRN cost between £100 and 125 million ($130 and 165 million) and Bepress may have cost between $100 million and $130 million. Mendeley and SSRN have business models which are unlikely to ever become truly profitable as standalone entities, while Bepress was profitable at the time of the acquisition (but the price paid still looks very expensive).

What is Elsevier’s strategy?

Elsevier’s answer to this question has probably evolved over time. As we previously mentioned, it is not unusual for a company to enter a business or acquire assets with one strategy in mind and then broaden its scope as it learns more about the opportunities offered by the acquired business and as the industry landscape evolves. Several interviews have surfaced four themes which we believe are central to the future of Elsevier.

-

Protect the core journal business. Elsevier must realize that Open Access (OA) is a significant threat to its economics, given that revenues per article today are in the region of £3,100/$4,100. Elsevier appears to have lowered its revenues/article over time (the total number of articles Elsevier publishes has grown by about 5% CAGR between 2006 and 2014, and reached about 430,000 in 2017), faster than its journal revenue growth of about 4% annually. Even so, Elsevier faces a potentially significant decline in revenues in the case that a full transition to OA takes place, since several surveys and reports indicate that the industry average APC is in the region of $2,250 to $2,400. Elsevier could cut some costs to compensate for lower revenues, but we estimate that, with current estimated costs per article in the region of $2,650, a 10-15% cut would only save about $250 to $400, well below the decline in revenues. Incidentally, research Bernstein conducted years ago with the collaboration of a scholarly journal publisher surfaced that a full transition to OA would lead to savings of 12.5% in its cost base, so a 10 to 15% cost reduction appears eminently reasonable. In this scenario, however, the operating profits of Elsevier would be wiped out almost completely, as both revenues and costs would converge around the $2,250 to $2,400 mark. The best way for Elsevier to protect its profitability to would be to gain a massive market share at the high end of the market that could and would pay for expensive APCs. This, in turn, would be easier if Elsevier could win larger and larger numbers of high quality submissions from authors. In this scenario, Elsevier might be able to publish more high impact articles thanks to early insights into the quality of research (for example, through access to the desktops of researchers through Mendeley).

-

Improve how Elsevier runs the journal business? Elsevier already holds one of the largest repositories of data on citations and readership through its various databases (from Scopus and Science Direct to Mendeley, SSRN, and Bepress). Simply put, the more data points Elsevier develops, the better it positions itself to gain insights into developments that will affect its competitive position in the future, often with an early advantage which may be measured in years. For example, Elsevier could identify, through the analysis of research and publication patterns and the quality and reach of their collaboration networks, which researchers are likely to grow into future leaders in their respective fields and offer them editorial board positions on their journals ahead of other publishers. Elsevier could also identify which segments of various disciplines are likely to evolve into the next growth area for research by looking (for example) at project participation patterns, size and quality of teams, and funding bodies’ decisions, targeting these segments with new, dedicated journals ahead of other publishers. Similarly, Elsevier could isolate in advance new trends in interdisciplinary studies, allowing it to establish publication forums where none exist today and even driving funding decisions which lead to accelerated growth for these types of research. Each of these levers could enhance the competitive position of Elsevier, particularly because the company has access to far more data on research patterns than any other publisher (except for Clarivate, which does not have access to content itself). In addition to these strategic opportunities, there are more tactical ones, which may allow the company to run its operations better and at lower costs. For example, Elsevier could identify the editors best suited to work with specific authors to accelerate manuscript editing, or which peers are likely to respond faster and more constructively to requests for peer review on the basis of specific characteristics of articles. The possibilities are many and the opportunity for smaller publishers to replicate these advantages is almost nil because of Elsevier’s size and reach in the marketplace.

-

Sell insights to universities, funding bodies and governments. The same insights that would allow Elsevier to offer editorial positions to rising star researchers or to launch new journals ahead of the competition are valuable to universities. Elsevier and Clarivate, as well as smaller competitors like Academic Analytics, already sell tools aimed at assessing the productivity of specific research. Some of these tools are relatively primitive, but it is reasonable to assume they will become better over time (interviews suggest that Clarivate is ahead of Elsevier in terms of quality, but Elsevier is working to fill the gap by offering to test their tools for free with leading research universities). In addition to driving resource allocation, these tools can also affect other core processes of universities. For example, the quality of published research (using the impact factor of journals as a proxy) has played a major role in hiring, promotion, and tenure decisions. Being able to better assess and predict the likely trajectory of Ph.D. candidates, research associates, and Assistant and Associate Professors would be of great value to the leadership of universities. Similarly, being able to target early on which emerging disciplines or subjects are most likely to grow in relevance (to the point of attracting significant incremental funding and students) would allow universities to improve the return on investment in new areas.

Moreover, once these tools are deployed, the customers may find it difficult to discontinue usage for several reasons, including equity considerations (using the same assessment tools over time is encouraged in people-related processes, and lack of transparency on how algorithms work would make it difficult to substitute them). In general, the experience of the corporate sector is that users tend to rely on specific third-party data and find it difficult to abandon once it is embedded in their core processes. This means that these services can generate recurring revenues with strong pricing power, and Elsevier is uniquely positioned to offer these services given its access to content and underlying data.

-

Sell insights to industry or the investment community. This opportunity may be the most speculative, but it is also, by far, the most valuable. Elsevier, like any other STM publisher, sits on a massive amount of intellectual insights and – increasingly – data. To provide some general estimates, NASDAQ believes that about 30% of its market capitalization (currently about $3 trillion out of a total capitalization of $10 trillion) is derived from academic research. It would make sense for Elsevier to try to capitalize on its early access to academic research (for example, by partnering with industry to exploit insights, or by establishing joint ventures with Venture Capital firms to improve the odds of VC investing).

Elsevier seems well aware of the value of text and data mining, as it effectively attempts to prohibit text and data mining of articles outside of its own tools. It is possible that Elsevier only thinks of monetizing this value through the licensing of software that allows third parties to data mine articles and data repositories. One step in this direction is Elsevier’s recent launch of its Entellect platform, a product targeted at life sciences companies that combines access to proprietary company data, Elsevier databases, and academic literature to mine text and data and streamline the R&D process. On the other hand, Elsevier may realize that much more value can be realized by mining the text and data by itself and then selling insights to interested third parties. Our interviews with industry participants indicate that Elsevier’s is unlikely to take such a bold step, but it is entirely possible that management will see the opportunity at some point.

What could derail Elsevier?

We see three major threats to Elsevier’s performance going forward and have laid them out below in what we estimate to be declining order of likelihood.

-

Failure to properly execute their data strategy. For all the competitive advantages which Elsevier has, their data strategy carries some risks as well. First and foremost, Elsevier is viewed with suspicion within large segments of the academic community. The launch of this SPARC project, for example, is the result of continuing ill will between Elsevier and the academic community. Elsevier has made several efforts to mend fences through a variety of approaches, ranging from donations and sponsorships of academic programs and events to the steady effort to communicate its support for research values through members of the academic community. Despite these efforts, Elsevier has made little headway, in part because – in parallel with these pacification efforts – it continues to lobby for additional copyright protection, it staunchly defends rights which are counter- intuitive to academics (like refusing to allow text and data mining of articles with third party software), and it continues to demand price increases that are viewed as unreasonable and ignore the financial constraints of academic libraries.

In addition to these issues, which may lead universities to exercise special care to control or cap the usage of Elsevier data tools and services, Clarivate appears to have a significant lead in the quality of its competing tools. Clarivate also has the following advantages: a reputation for independence, no journal business to protect, and ample funding to maintain their current high-quality leadership. Lastly, Clarivate has the advantage of carrying an Intellectual Property business in its portfolio, which may make it the natural winner in selling services tied to IP exploitation.

-

A sudden collapse of subscription publishing. Historically, shifts in the scholarly communications industry have taken place at a glacial pace. Open access (OA) revenues were still less than $500 million in 2017, or about 5% of total industry revenues, 15 years after the Budapest Open Access Declaration was signed. Of course, revenues undercount the extent of the success of OA because they do not include articles funded in OA through other programs, or the large number of articles made available in OA through repositories rather than journals – the articles available in OA in any form are now closer to 30% annually and rising. However, revenue is what has traditionally mattered to subscription publishers.

Nonetheless, a collapse cannot be ruled out completely. Should governments and private funding bodies in the U.S., Japan, and Western Europe agree to abandon embargo periods before mandatory deposit in open repositories as well as disqualify hybrid journals from fulfilling OA mandates (and prove willing to enforce their mandates by publicly excluding violators from future grants), publishers may see submissions to all but a handful of leading journals dry up quickly. The industry may then convert to a pure Gold OA model to secure revenues, but – as mentioned earlier – the relatively high cost structure of Elsevier leaves it poorly equipped to compete in a Gold OA industry. If this were to transpire, Elsevier would have to go through a lengthy period of restructuring, and – in the meanwhile – financial markets would likely show their displeasure by shrinking the valuation of RELX Group, both because Elsevier earnings would collapse and because it would be difficult to see a path to recovery.

Plan S may or may not lead to a full OA transition. The number (and spending) of the initial supporters is relatively modest, but more countries and funding bodies are expressing an interest in joining, at least in principle. Important issues remain open, however. Will a transition phase, allowing the publication of OA articles in hybrid journal, be allowed or not? For how long? What will trigger the sunset of such phase? Similarly, will caps to APCs be imposed? For how long? At what level? Just to be clear, an indefinitely long transition phase and/or the removal of any APC caps would decrease the impact of Plan S on subscription publishing; conversely, the outright banning of hybrid journals and the imposition of low caps on APCs would dramatically change the publishing landscape.

In addition, piracy might force a change in the business model. While librarians are careful to point out that using Sci-Hub is not legal and that there are better (and legal) alternatives, awareness of Sci-Hub continues to grow. Elsevier has been at the forefront of legal action to squash Sci-Hub, but efforts, so far, have not been effective. The experience of other media business – first and foremost the recorded music industry – suggest that it is close to impossible to litigate violators of copyright out of existence, since they can take refuge in jurisdictions outside the reach of Western courts, and, even when a company is finally taken down, a new one can quickly rise to take its place, starting a new cycle of litigation. The lesson from the music industry should not be lost on the management of Elsevier (and other publishers): what finally put peer-to-peer services out of business was not a recourse to legal action or technical mechanisms to foil searches, but the introduction of music streaming services which offered a convenient, reasonably priced service that satisfied consumers. In this sense, the scholarly communications industry is fortunate to have a model ready at hand to adopt – OA – rather than needing to look for one and test it. It took about 15 years between the revenue peak of 1999 and the widespread adoption of Spotify for the music industry to find a way out of its decline, and it had the good fortune of finding two companies (Spotify and Apple) willing to incur losses for several years to launch and grow the service.

We pointed out earlier that Elsevier’s best defense in a fully OA world would be to win a disproportionate amount of high-quality submissions through predictive analytics. The other tool available to mitigate the impact of a shift to OA would be to add more value to articles than what other publishers can provide. Elsevier could try to facilitate search and access, streamline and accelerate editing and peer review, add personal recommendation and sharing tools, and justify higher APCs through demonstrable better usability of its journals and platforms. It is not by chance that Elsevier acquired Plum Analytics in February 2017, a leading provider of altmetrics, as well as Aries Systems (this deal was announced just at the beginning of August 2018). It would make sense for Elsevier to develop deep insights into how articles are used and demonstrate to researchers, funding bodies, and departmental heads the value of publishing with Elsevier (assuming, of course, that such value is demonstrable) to avoid being dragged in price competition with cheaper OA journals.

-

Goverment Intervention. Even if the current hybrid system remains in place, it is questionable why Elsevier refuses to enter offsetting deals in most countries. It is difficult to believe that governments offering subsidies for Gold OA publishing (as it happens in Western Europe) intend them as a mechanism aimed at increasing publishers’ revenues at the expense of taxpayers. It is a relatively minor issue compared to taxpayer subsidies of the energy or banking sectors, and it is unlikely to excite a populist backlash against Elsevier. On the other hand, because it is a somewhat arcane topic, it could be sufficient to find a handful of legislators or politicians in one country to adopt the cause and push for tough action. This could take many forms, such as excluding publishers who refuse to sign offset deals from receiving public funding for APCs or barring Elsevier from public contracts. Any governmental action would be litigated in court and would introduce further uncertainty and create a reputational risk which could affect the share price of Elsevier and force it to change course of action on OA.

Similarly, Elsevier could be subject to anti-trust action. A complaint was lodged in October 2018 with the European Commission, alleging that RELX practices violate two articles of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union. Whether the European competition authorities will pursue the case remains unclear at this stage, but the expansion of Elsevier’s activities into the provision of data analytics back to universities may raise further concerns.

-

Revenues per article at Elsevier should be in the region of £3,100/$4,100 per article (we derive this number by taking 55% of the reported Elsevier revenues, which derive from journals, and dividing them by the 430,000 articles which, in 2018, Elsevier claimed it publishes every year). By comparison, the then CEO of Springer guided informally a few years ago in a meeting with investors that Springer (before the Nature Publishing Group merger) was earning about €2,000/$2,300 per article. This number will have risen thanks to the merger with Nature; at the same time, Elsevier has been lowering revenues per article. As a result, the gap is likely closing. ↩