Market Changes in the Context of the COVID-19 Crisis

At the time of writing in May 2020, it is very difficult to formulate any realistic forecast in terms of the impact of the health and economic crisis on the markets covered by the Landscape Analysis. The impact of COVID-19 on the global economy, in particular on the United States and Canada, is starting to emerge only now; the range of forecasts both for the depth of the recession and for the shape and length of the recovery are just attempts to provide some guidance. Forecasts for the decline of the US GDP in Q2 2020 range from 10%1 to 50%2, a span so wide as to be essentially meaningless; forecasts for Canada show a similarly dreadful span (-15%3 to -30%4).

The range of outcomes that could emerge from such broad uncertainty is vast. It is impossible to compile an exhaustive list of the uncertainties; however, a short list includes:

- Economic uncertainty

- Higher education-specific uncertainties (what will happen to budgets and students/classes)

- Industry uncertainties (the responses of commercial vendors)

- Regulatory uncertainty (such as mandates for immediate OA of academic articles based on publicly funded research).

A document that effectively captures many of these issues is the letter that Ronald J. Daniels, President of Johns Hopkins University (JHU), sent to the JHU community5 explaining COVID’s impact on the institution and how JHU plan to address that impact.

One of the lessons of the 2008 subprime crisis and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis of 2011 is that every major crisis is different. Nonetheless, it is possible to review what we do know – and what we know we don’t know.

In general terms, the most significant unknown is the duration of the COVID-19 crisis. Until now, most countries have elected to issue short-term rather than long-term travel bans and stay-at-home orders. At this point, it is impossible to formulate realistic timelines; while there is always the hope of bringing the pandemic under control sooner rather than later, the psychological impact of issuing long-term bans would probably aggravate the economic downturn.

Financial markets are trying to predict whether the global economy (as well as the economy of the wealthiest countries) will experience a V-, U- or L-shaped recovery. These terms indicate, respectively, a very fast rebound, a period of stagnation at lower levels of activity before recovery starts, or a long period of depressed economic activity. The high volatility in the equity markets reflects how uncertain any of these scenarios is, and it is virtually useless to make predictions today.

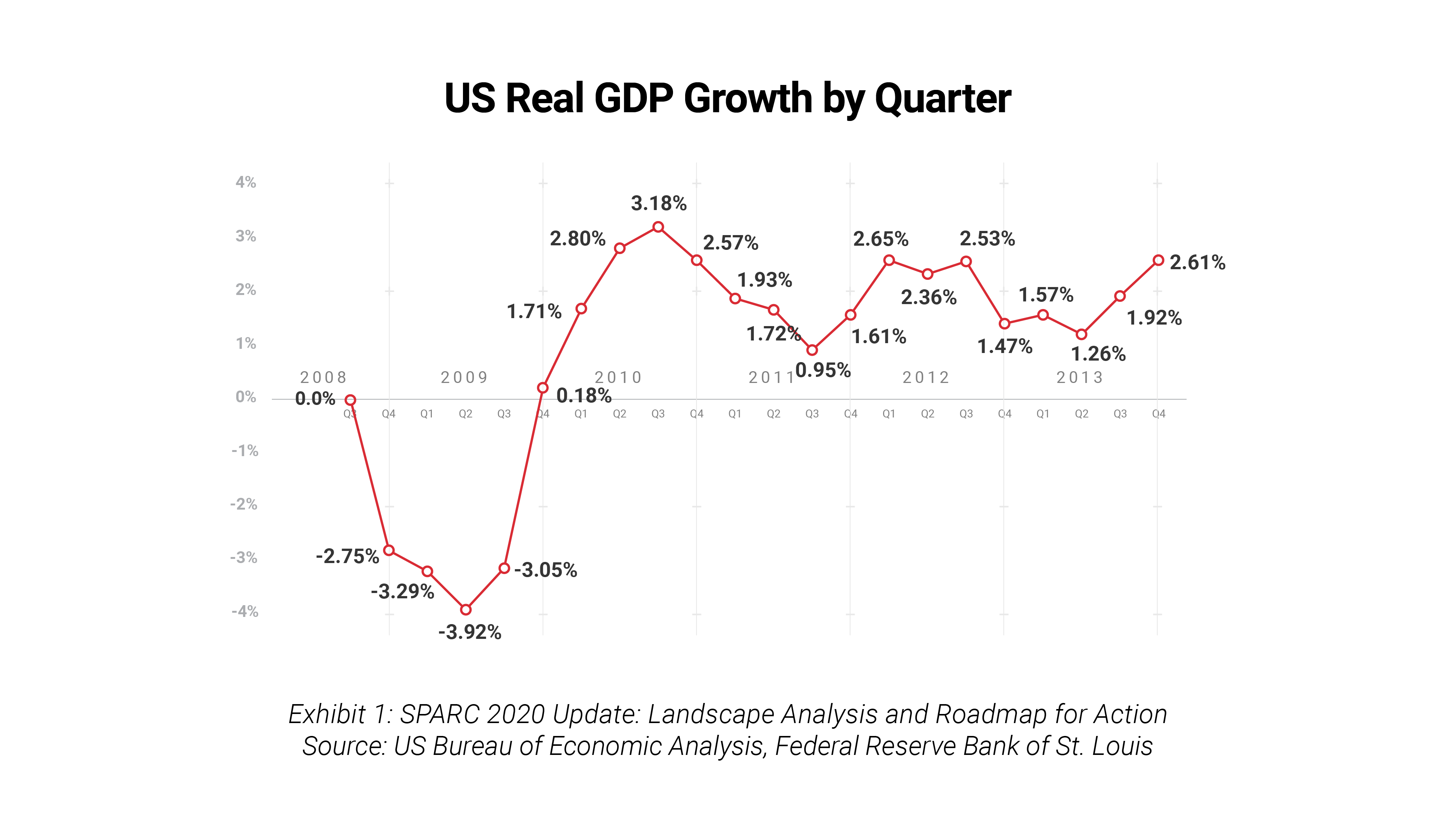

Past experience, however, shows that the willingness to provide incremental relief to support prolonged growth tends to decline once recovery sets in. Looking at US GDP growth, we see that after the financial crisis of Q3 2008, the US economy did not return to growth until Q4 2009 (Exhibit 1). Growth then accelerated for three quarters before starting to decline again. Therefore, even in a “V-shaped” scenario, after an initial lag, recovery would be fast but then possibly slow down again relatively soon – what some economists call a W-shaped recovery.

A more pessimistic scenario suggests that it will take until sometime in 2021 to bring the pandemic under control, aggravating the economic impact well beyond what current stimulus programs launched in various regions of the world can cope with. In this case, the survival of many companies will be a function of the willingness of governments to support them with further cash. This will probably need to take the form of direct subsidies and grants or even de facto nationalization (partial or total), should the cash be disbursed in exchange for equity. Because of the uncertainty surrounding the likely depth and length of the recession, this may not be the best time for companies to head into a collision course with their respective governments, since they may become dependent on rescue programs for their survival.

The Impact on Scholarly Journal Publishers

In the near term, scholarly journal publishers seem to believe that subscription revenues will be partially insulated by their long-term contracts with academic libraries.6 However, the leading commercial publishers may be overly optimistic in formulating their outlook. Management teams may well be basing these relatively upbeat statements on the experience of the 2008 financial crisis: RELX’s STM business, for example, delivered organic revenue growth of +4% and +2% in 2009 and 2010, respectively. With an average contract length ranging between three and five years, management teams may be assuming that many academic libraries will cope with shrinking budgets by cutting other services first, rather than by stopping payments on their existing subscriptions. On the other hand, some libraries have “financial hardship” clauses they may decide to trigger, while the ones that have contracts expiring in 2020 and 2021 may well decide to demand significantly lower spending, or even choose to abandon collection subscriptions altogether to save cash.

Going forward, academic libraries will likely demand more favorable conditions when renewing their contracts, and signing complex transformative deals may take longer than it already does. The crisis will exacerbate the problem of radically reallocating costs to “publish-intensive” institutions inherent in “transformative” agreements. Ultimately, this crisis may well lead to a reckoning: the price and value of collection subscriptions have become so misaligned that the current spending levels may not be sustainable when facing library budget cuts. Once a clearer view of post-COVID budgets emerges, the incentive to abandon collections subscriptions and acquire a much smaller number of leading titles from each publisher will likely grow.

The uncertainty surrounding COVID-19’s impact on research funding may well affect open access publishing specifically. A possible decline both in the number of new grants for research and in their individual size may put more pressure on funding APCs, adding further questions about the sustainability of APC-based Gold OA, even in the limited number of disciplines for which the model is suited. However, the launch or expansion of major research programs in life sciences and in viruses in particular could offset some of the possible decline in funding for research, and limit the negative impact on the volume growth of OA articles (although some publishers, like SAGE, have waived APCs on COVID-19-related OA articles). There may also be an additional negative impact on the capacity of academic libraries to sustain monographs, through either the purchase of print editions or the funding of OA digital editions.

Risks posed to the subscription model by COVID-19 are both structural and reputational. While many publishers tried to move quickly to introduce some form of emergency program to open up COVID-19-related articles, the structural difficulties of trying to selectively open up content in a system that is closed by default quickly became apparent. An article by Vincent Larivière, Fei Shu and Cassidy Sugimoto documented the results of the Wellcome Trust’s January 31st request for publishers to make all of their COVID-19-related papers fully open access.7 By March 5th, over half (51.5%) of the articles published on coronavirus since the late 1960s (according to the Web of Science) still remained closed.

The Wellcome Trust’s experience is far from unique. In mid-March, a group of National Science and Health Advisors from 12 countries, including the US, issued a further request to publishers to enable researchers to “access, re-use and text mine” all papers relevant to the coronavirus from a single database. Publisher response was again mixed, with some quickly providing full open access to their articles but many others providing only temporary access limited by bespoke licenses – and still others not providing their articles at all.

This incident highlights the inherent problem of the readers/users of scholarly articles having to routinely seek individual publisher permission in order to conduct basic research. It also raises the question: if open access to articles and data is better and can save lives, why should it happen only at exceptional times? Surely, patients struggling with other diseases – cancer, heart disease, etc. – are as deserving of help as coronavirus patients?

This is also playing out at a time when publishers’ value-added practices are under particularly intense scrutiny, and under the threat of a possible Executive Order in the US mandating that all federally funded research be made openly available without embargo. The inadequacy of the publishers’ response illustrates the irreconcilable tension between the effective communication of science/scholarship and gated access models.

The Impact on Courseware Publishers

The outcome of the crisis for courseware publishers is much harder to forecast, as it is reasonable to formulate scenarios with very different implications.

A crisis that extends into the second half of 2020 will likely lead to a drop in enrollment, as many academic institutions may choose to keep their physical doors closed for another semester, making it more likely for students to defer their attendance until they can return to campus. Historically, recessions have been good for college enrollment (and for textbook publishers): Pearson estimated, in the aftermath of the 2009 recession and the subsequent recovery, that a 1% change in the US unemployment rate would drive a 3% change (in the same direction) in college enrollment. However, this relationship is likely to break down if college doors remain closed.

A significant number of students may be willing to shift to online courses and even online degrees, but it is unclear how many colleges are equipped to run a fully online program, including tutoring students, administering exams securely, etc. Some publishers (Pearson, Wiley) have strong capabilities in running online college programs, and may benefit more than others from enabling colleges to move to offering online classes and degrees. On March 23rd, 2020, Pearson issued a trading update indicating that it was seeing a substantial increase of interest in virtual schooling. The trading update referred specifically to Connections Academy, its K-12 virtual school, but the same trends may unfold for higher education as well. We will come back to the issues posed by a significant shift to online.

The Impact of Debt on Academic Publishers

Finally, the threat of a major recession has a significant and asymmetrical impact on companies on the basis of their debt profile. To illustrate this, we will use the latest reported Net Debt/EBITDA ratios for the companies covered in the Landscape Analysis. EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization) is a commonly used indicator of the cash earnings generated by a business, and Net Debt/EBITDA is a commonly used measure of debt. While there is no standard definition of an excessive Net Debt/EBITDA ratio, ratios above 3.5x are considered quite high.

-

https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us-news/en/articles/news-and-expertise/the-economic-impact-ofcoronavirus-202003.html ↩

-

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-22/fed-s-bullard-says-u-s-jobless-ratemay-soar-to-30-in-2q ↩

-

https://www.fool.ca/2020/05/04/coronavirus-recession-should-you-sell-your-stocks-now/ ↩

-

https://www.fxstreet.com/news/canada-gdp-growth-is-pegged-at-48-for-2020-nbf-202004071335 ↩

-

https://hub.jhu.edu/novel-coronavirus-information/financial-implications-and-planning/ ↩

-

For example, in April 2020, giving its following full year outlook for the STM business, RELX stated: “Positive revenue momentum continued through the first quarter. As we go through the year, we could see some impact from the COVID-19 pandemic in our customer markets, and prolonged restrictions on movement could potentially impact our ability to conduct new sales in person and distribute print products, but overall revenue stability is supported by 75% being subscription based.” Also in early April, Wiley communicated to investors that Q4 revenues would be affected by “delays in closing annual journal subscription agreements in certain parts of Europe and Asia due to challenges of remote selling and university disruption. … Wiley estimates that approximately one-quarter of the fourth quarter revenue and earnings impact from COVID-19 is timing related, primarily in Research, and recovery is expected in subsequent periods.” ↩

-

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2020/03/05/the-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreakhighlights-serious-deficiencies-in-scholarly-communication/ ↩